Despite the 50 times she’s been intubated and the two times she came close to death, Alison Clay, MD, FCCP, AISF, Assistant Dean for Clinical Education at Duke University School of Medicine, says the worst side effect from her time in the intensive care unit (ICU) is mistrust in the healthcare system. During a Grand Rounds presentation earlier this month, “Delirium: Dreams, Distress and Deterrence: A patient and provider perspective,” Clay detailed the treatment she received as a patient.

Clay cited a study in which patients report feeling like they are being drowned,

suffocated, or assaulted by the providers during their time in the ICU. Clay, who has a chronic illness, described experiencing this first-hand every time she’s admitted to the ICU. Half of patients and a third of family members, she said, also report sleep deprivation and a loss of control during their time in the ICU.

“I would propose that patients with chronic illnesses . . . are like canaries in the mines of our health systems,” Clay said. “They are the ones who are going to find the problems because they experience the healthcare system frequently.”

Clay has oxidative phosphorylation disorder, a neurodegenerative and chronic illness that results in a lack of ATP during physiological stress and suppresses the function of the brain, nerves, skeletal and cardiac muscle, and more. Following an elective surgery, Clay contracted a post-operation fever, but her body did not produce enough ATP to fight off the illness, landing her in the ICU once again.

Clay detailed one experience in particular in which she needed to be intubated, the panic  caused by a room suddenly full of people, the feeling of being smothered by the Ambu bag, and the “extremely terrifying” restraints necessary to prevent sudden patient extubation. “I feel like I am suffocating as they prepare to intubate me, and nobody is paying attention to how I feel because everybody is paying attention to the monitors.”

caused by a room suddenly full of people, the feeling of being smothered by the Ambu bag, and the “extremely terrifying” restraints necessary to prevent sudden patient extubation. “I feel like I am suffocating as they prepare to intubate me, and nobody is paying attention to how I feel because everybody is paying attention to the monitors.”

In this particular example, Clay said she entered a state of delirium in which she believed the team was purposefully trying to cause her pain. She stayed awake for 96 hours straight, afraid of what would happen if she closed her eyes. All of these experiences in the ICU and more like them, she said, are common and preventable.

Even after recovery and release, staff in ICUs often provide insufficient information to help patients transition from hospitals to life at home. For example, Clay says physical therapists rarely prepares people for going up and down steps, a common skill needed to move around a home. And when it comes to transition of care, Clay cited a study which found only 20% of patients knew how to pass on information from the hospital providers to their primary care providers.

“We just don’t have good mechanisms for who can serve as bridge to patients in those moments of terror by yourself at home,” Clay said.

To resolve these problems, Clay suggests providers focus on improving communications by recognizing the patient’s vulnerability in their situation. Clay says providers should first look at the person in the bed and understand what they are feeling rather than viewing them as a set of numbers.

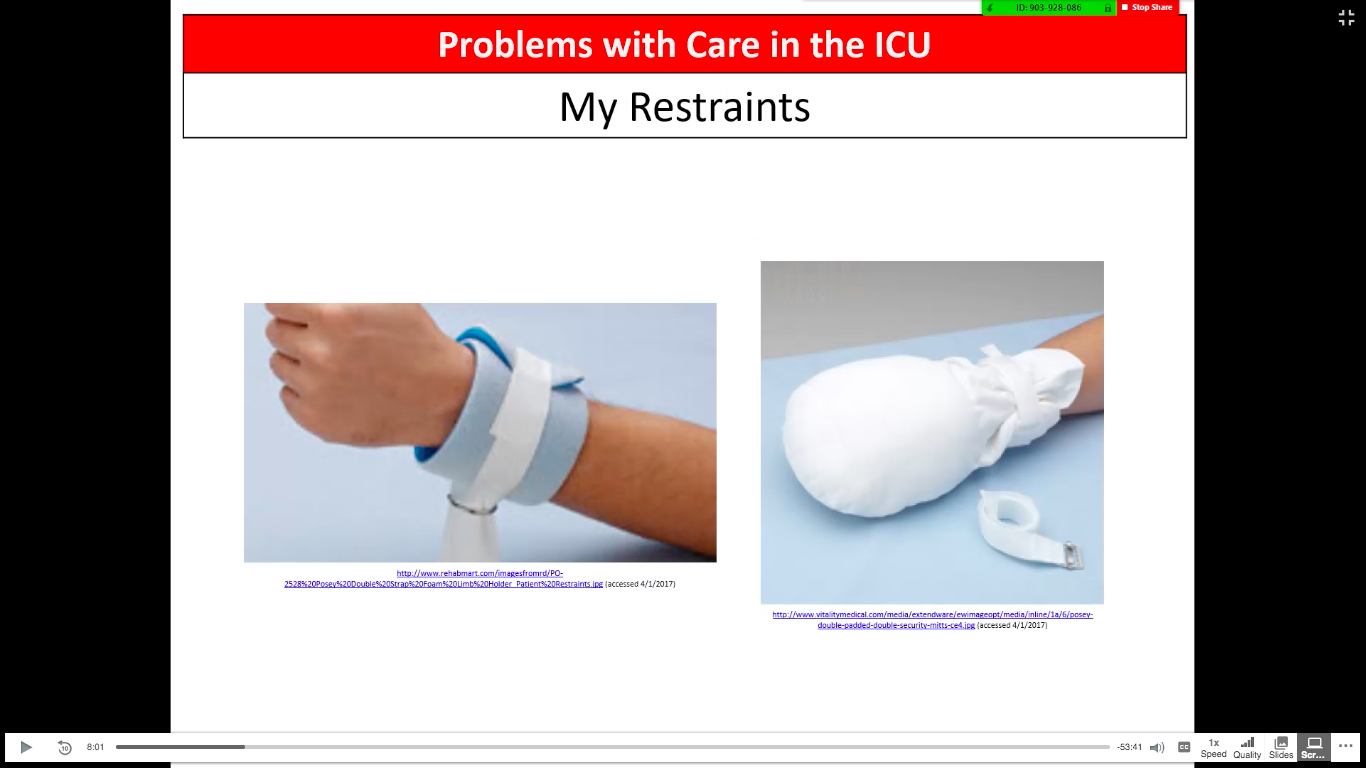

As a provider herself, Clay has tried to remember that little details doctors and nurses  attended to around her mattered to her wellbeing while a patient. Whether it was cleaning trash off the floor or “scrubbing the hub” for at least 30 seconds, these small tasks assured Clay she was in good hands. Studies have found, she reminded the audience, just sitting down to talk can help increase understanding and leave a patient more satisfied with the conversation. Other practical suggestions included recording voice memos for patients and families to help them recall discharge instructions.

attended to around her mattered to her wellbeing while a patient. Whether it was cleaning trash off the floor or “scrubbing the hub” for at least 30 seconds, these small tasks assured Clay she was in good hands. Studies have found, she reminded the audience, just sitting down to talk can help increase understanding and leave a patient more satisfied with the conversation. Other practical suggestions included recording voice memos for patients and families to help them recall discharge instructions.

Clay encouraged her audience to continually ask for feedback and for suggestions from patients to make sure they are feeling comfortable and cognitively and emotionally supported during their time in the ICU. At Duke University, Clay said she and other providers teach their students the Ask-Tell-Ask technique where providers first ask how the patient is, then tell the patient new information, and finally ask the patient about their understanding of the next steps.

“There’s a neurologist in our institution where every day he asks patients ‘what can I do today to make your day better?’” Clay said. “Especially when you’ve been in the unit it’s helpful acknowledgement the days run into each other and it’s partnering with a patient to say ‘I just want to do something better.’ Because most of what is most disturbing to me as a patient isn’t the physical. It’s the emotional, spiritual, and social suffering that happens through critical illness.”

Following Clay’s presentation, Loreen Herwaldt, MD, professor in Infectious Diseases and of Epidemiology, said that as an outpatient provider, she plans to ask her patients more about their emotional and cognitive state during their post-ICU visits.

“Delirium has serious long-term consequences,” Herwaldt said. “It is important to take the patient seriously because the patients know their own bodies.”